DNS Service Discovery is a way of using standard DNS programming interfaces, servers, and packet formats to browse the network for services.

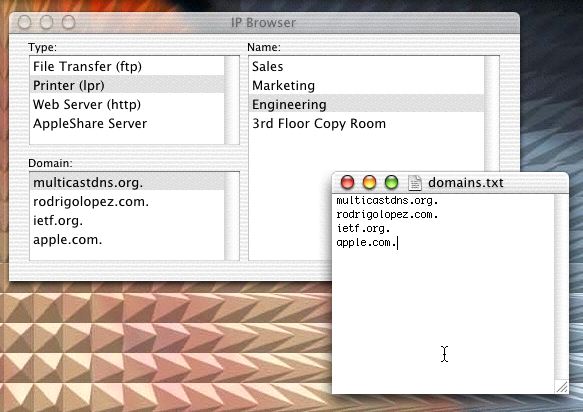

If you think the picture below looks a lot like the old Macintosh AppleTalk “Chooser”, that’s no coincidence. As we move away from AppleTalk to an all-IP world, we don’t want to have to give up the convenience and ease of use that made AppleTalk popular, and made AppleTalk continue to be popular long after it should rightfully have been retired.

DNS Service Discovery is compatible with, but not dependent on, Multicast DNS.

One of easiest applications of Wide-Area DNS-SD is simply to add a few records to your domain’s authoritative DNS server(s), to automatically advertise selected services to clients, with zero configuration on the client side.

When clients get a response packet from the local network’s DHCP server, there’s a domain in that packet, and clients running Mac OS X 10.4 (Tiger) or later, or iOS, or Bonjour for Windows, automatically query that domain for advertised services. Therefore, as long as you have administrative access to that domain’s authoritative DNS server(s), you can easily add the necessary records so the clients will discover web pages, printers, and other network services of your choosing. If you don’t have have administrative access to the domain currently being returned by your DHCP server, but you do control the DHCP server, then you can change the DHCP server to return a different domain — one that you do have control over. In many cases people set their home gateway’s DHCP server to return their ISP’s domain name in the DHCP packet, without giving it much thought. There’s really no reason to do this, since you have no control over your ISP’s domain. It makes a lot more sense and is a lot more useful to set the domain to be one that you do have control over.

A common misperception is that the service discovery records need to be created on a DNS server that the service discovery client is configured to use. Or, conversely, that the client needs to be configured to use the DNS server where the service discovery records exist. This is not correct. To look up the address of “www.amazon.com” you don’t need to first configure your client to use Amazon’s DNS servers. To look up the address of “www.google.com” you don’t need to first configure your client to use Google’s DNS servers. Just like looking up addresses, to discover services advertised in a given domain you don’t need to first configure your client to use that domain’s DNS servers. This is the beauty of DNS. The answer to a DNS question depends (generally speaking) only on what the question is, not which server you ask. You can send your DNS question to any DNS server in the world, and (generally speaking) always get the same answer for your question. This common misperception about DNS-SD stems from the fact that the term “DNS server” is used to refer to two very different things. Historically this is because “named” (the name dæmon software) could could perform both functions, and when they used the term “DNS server” experienced DNS operators instinctively knew which function they were talking about. The distinction has been less clear to people who are not experienced DNS operators. The first function of the “named” software is to be an authoritative name server for a domain. This is the ultimate repository where DNS information about a domain resides. The authoritative name server function may be replicated for reliability — i.e., there may be several authoritative name servers for a given domain, all with the same DNS record data. Typical clients never communicate directly with authoritative name servers. The second function of the “named” software is to be a recursive resolver. Typical clients send their queries to their configured recursive resolver. That recursive resolver may return answers it had previously cached (hence its other common name, “caching resolver”) or may communicate with one or more authoritative name servers on the client’s behalf. This may require multiple round-trips to multiple authoritative name servers to determine which authoritative name server, somewhere on the planet, holds the answers the client seeks. Once the recursive resolver has retrieved the requested answers, it sends them to the client.

To deploy DNS-SD, clients do not need to be configured to use a different recursive resolver, and no changes are required on the recursive resolver the clients are using. The configuration the clients need is not who to ask, but what to ask. The clients need to know in which domain to look for services, not which recursive resolver to ask. Fortunately, in most cases, the necessary configuration is already present. When clients get a response packet from the local network’s DHCP server, there’s a “domain” parameter in that packet, and it’s typically used as the client’s default DNS search domain. DNS-SD clients also use it to discover their default DNS service discovery domain. So, in most cases, all the required client configuration is already in place. What remains is simply to add a few service discovery records to the authoritative name server(s) for the domain given in the client’s DHCP configuration.

There are two ways to experiment with adding service discovery records to your authoritative name server. If you have your own authoritative name server already set up and running, you can just add the necessary records. A common use of this is to facilitate Wide-Area AirPrint discovery. If you don’t already have your own authoritative name server, or you do but don’t want to put the records there just yet, then you can also set up a temporary test server to experiment with the technology.

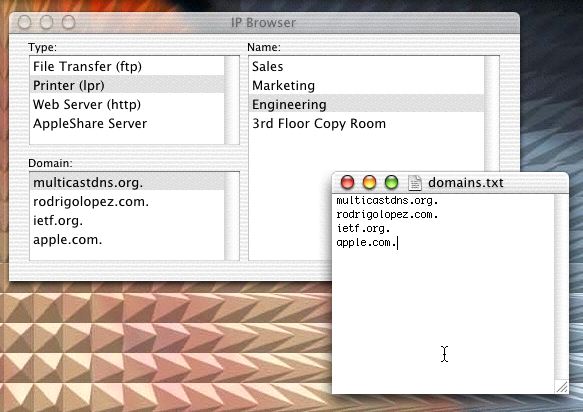

If you’re an end user and you don’t have access to a DNS server to experiment with, you can still see Wide-Area Bonjour browsing in action just by entering an appropriate DNS search domain.

After advertising static services to clients, the next step you can take, if you choose, is to allow clients to advertise their own wide-area services.

Doing this is not zero configuration on the client side, for a couple of security reasons. One is that users of client machines on your network may not want their services advertised, potentially world-wide, without their knowledge or consent. For this reason, advertising of services into the global DNS is an option that has to be explicitly enabled by the client. In addition the client needs to specify the domain into which they want their services advertised. On the server side there’s also a security concern. On the world wide Internet, you can’t allow just anyone to update your DNS server. This means that the clients need to have cryptographic security credentials that establish their authority to update the domain in question. This means that clients need three pieces of configuration information:

Allowing clients to advertise services is a two-part task: